TOKYO, 16 Oct - How should Ireland deal with the attacking threat of the All Blacks? How do you devise a game plan to combat their instinctive brilliance? These are questions that have been asked for 114 years, ever since the first New Zealand team arrived by boat on Irish shores.

The coaches of countless Irish teams have wrestled with the problem since 1905, but only two men have solved it. Recently, Joe Schmidt has twice plotted a winning course – in 2016 and 2018 – but Tom Kiernan cracked it long before him.

In 1978, Kiernan's Munster team beat the All Blacks 12-0 at Thomond Park in Limerick, before an official attendance of 12,000. Famously, around 100,000 people claimed they were there. "Ninety thousand of them are liars," said Gerry McLoughlin, Munster’s loose-head prop that day. "Imagine lying to your grandchildren about a rugby match."

New Zealand won 17 of 18 games on that tour and achieved a first Grand Slam against the home nations, but 41 years on their lone defeat is the only game that is still talked about.

Nobody gave Munster a prayer against a strong All Blacks team that included most of their stars from that era, including Graham Mourie, Stu Wilson, Bryan Williams and Andy Haden.

The night before the game, using one of only two video recorders that existed in Limerick in 1978, Kiernan showed his players highlights of some of the All Blacks’ earlier victories. An unbeaten tour seemed a certainty. They were "cutting through British rugby like an armoured division piercing thin lines of infantry", wrote Clem Thomas in The Observer.

"I was petrified," said Tony Ward, Munster’s fly-half. "The question running through my mind was: ‘Do we have the right to be on the same pitch as these guys? Just looking at them on a television screen, all in black, was enough to unnerve me."

Rugby has evolved enormously since 1978, but some things do not change. There were striking similarities between the approaches of Kiernan and Schmidt in preparing teams to beat the All Blacks, not least a relentless, obsessive focus on the challenge ahead.

How did Munster – beaten 33-7 by Middlesex only five weeks before – pull it off? McLoughlin gives most of the credit to their coach, who as a player had come agonisingly close to beating New Zealand more than once.

"The only man who believed we could win was Tom Kiernan. They called him the Grey Fox. He could make you believe no team was unbeatable. Not even the All Blacks."

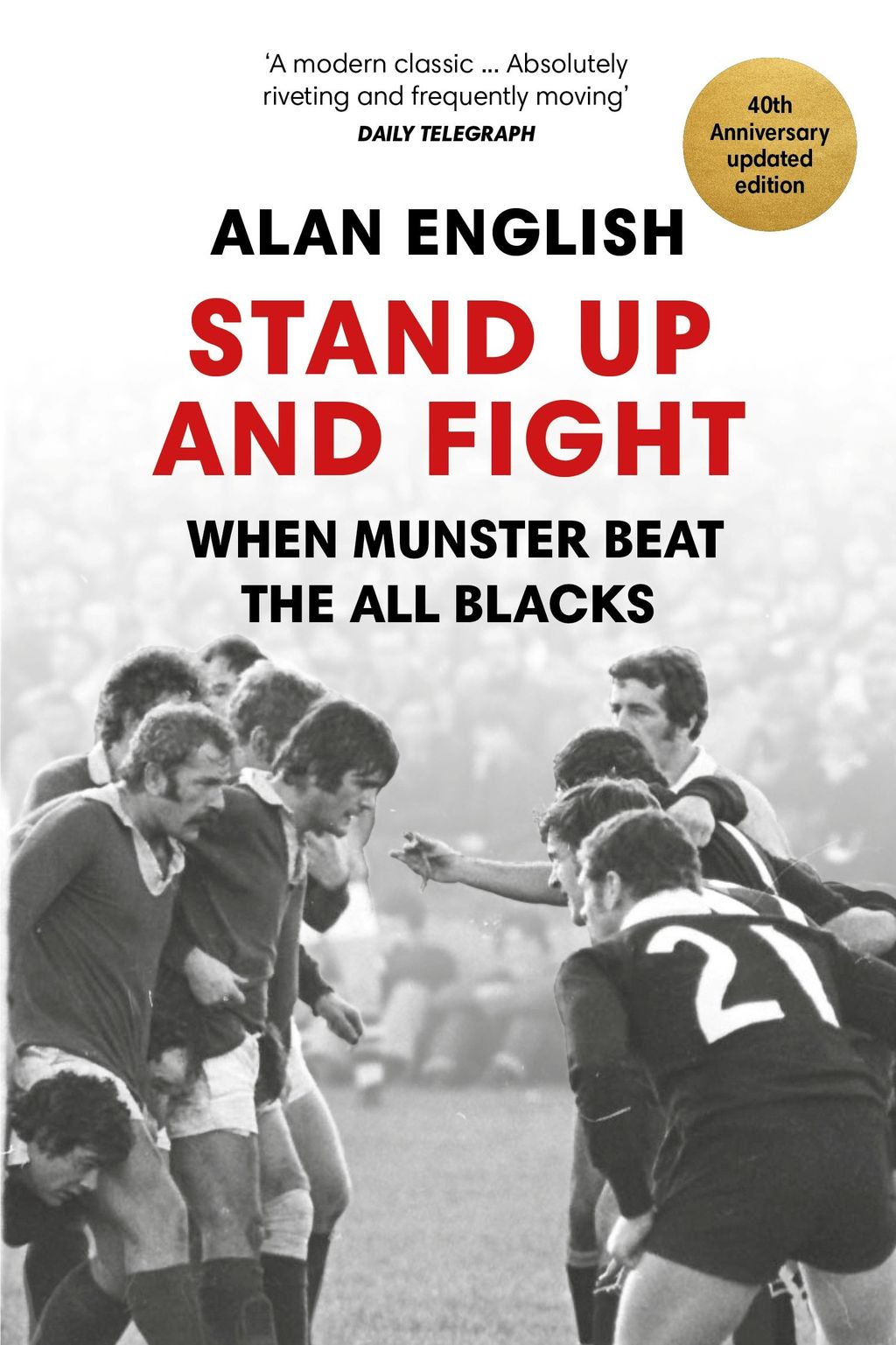

McLoughlin, aka 'Locky', was one of the central characters of Stand Up and Fight, my book about that game. In writing it, I also tried to explain why rugby came to matter so much to the people of Limerick, my home city.

"Rugby was life in Limerick," said the hellraising actor Richard Harris, one of our most famous sons. "The heroes of Limerick rugby are my heroes. Gladiators, square-jawed warriors who represent us on the battlefield."

The love for the game so evident in Limerick these days, the passion that feeds the legend of Munster and the All Blacks, has its roots in misery. Rugby was introduced to the city in the 1870s at a time when a mostly working-class population had no other leisure outlets.

Rugby lifted the city off its knees. Many of those who had been born in slums found there was a point to life, other than surviving it, and rugby played its part in this transformation. In the influence it had on local life, rugby had only one equal: the Catholic Church.

Over three years, I interviewed more than 150 people for the book and many of them shared an enduring fascination with the mystique of the All Blacks and their ability to rescue themselves when defeat seemed certain.

Through mostly bitter experience, Irish teams have learned that you can get on top of them, sometimes, but that is never enough: you must keep driving on. Even when his team were 12 points ahead with five minutes left – in an era when a try was worth only four points – Kiernan still looked like the most agitated man in Thomond Park. "We'd seen it go wrong too often. I couldn’t relax."

Thirty-five years later, Schmidt knew what that felt like. In only his third game as Ireland coach, he saw New Zealand overturn a 19-point deficit through a converted Ryan Crotty try, with the clock in red.

What Kiernan knew about winning, he learned from losing – especially against New Zealand. Likewise, Schmidt reviewed that 2013 defeat with his forensic eye and learned from it, which is why he was able to celebrate a famous win over the All Blacks in Chicago in 2016, pictured.

Between now and Saturday, as Ireland seek a place in the last four for the first time, many will have a view on how he might mastermind a third victory against Steve Hansen's team. That is another thing that does not change, when Irish teams come up against the All Blacks.

Back in 1905, when the team known to history as The Originals blitzed their way through British and Irish rugby, even the Limerick Leader got in on the act, on the eve of Munster’s first encounter with the "bewildering" All Blacks.

"Is it better to try to imitate their style, or to stick to the traditional Irish game and play it for all it is worth?" asked the Leader's correspondent. "The proper thing would be to play the ordinary game and put as much devil into it as possible. Try and smother them, and give them as few opportunities to pass as possible."

Munster lost that game 33-0, but more than a century later that analysis could apply to what awaits at Tokyo Stadium. Ireland, like the Munster of 1978, will have to stand up and fight.

Photographs by Michael Cowhey

RNS ae/bo/pp