Latest

-

![]()

RWC 2027 The best rugby players in the world revealed by RugbyPass

Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 will bring the best rugby players in the world to Australia, from stars of the Guinness Men’s Six Nations to those who’ve been tearing it up in The Rugby Championship, and beyond.

-

![]()

World Rugby World Rugby reaffirms support for global refugee community

Today, as part of the Sport for Refugees Coalition, we’re proud to reaffirm the vital role of sport in supporting refugees and host communities. Our joint statement calls on governments, donors, sports bodies, and humanitarian actors to embed sport more fully in refugee responses, ahead of the Global Refugee Forum Progress Review.

-

![]()

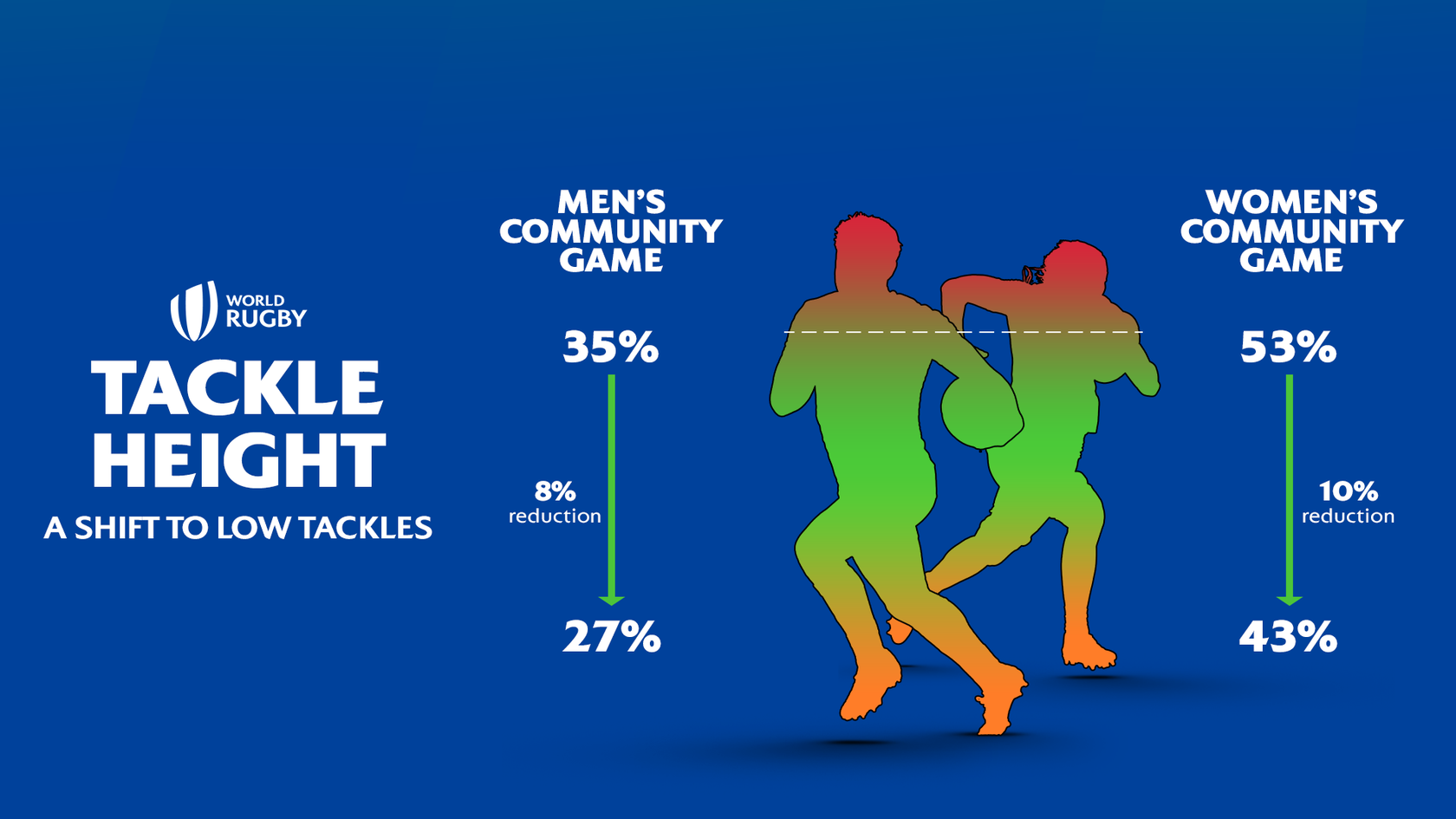

Player Welfare World Rugby Executive Board recommends that a lower tackle height be written into community game law

The World Rugby Executive Board has recommended that a lower legal tackle height at the sternum is made a full law of the community game. The move was proposed by the 11 unions who have been participating in trials of the measure over the last 18 months.

-

![]()

SVNS HSBC SVNS returns to Cape Town

HSBC SVNS arrives in Cape Town this weekend as the world’s top sevens teams continue their campaign following an action-packed opening round in Dubai. The event marks 10 years since the city first hosted the tournament in 2015, adding an important milestone to the series calendar.

-

![]()

EDITOR'S PICK RWC 2027 Draw: Quotes of the Day

Our pick of the quotes as coaches, captains and former stars react to the Draw for Rugby World Cup 2027 in Australia.

-

![]()

RWC 2027 RWC 2027 Draw: A closer look at the pools

With the Men's Rugby World Cup 2027 Draw now made, we take a deeper dive into each of the six pools.

-

![]()

RWC 2027 Pools confirmed for Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 in Australia

Preparations for Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 reached an important milestone today with confirmation of the six pools that will headline the largest tournament in the sport's history.

-

![]()

RWC 2027 Australia ready to ‘Go All Out’ with blockbuster global campaign for Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027

Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 has ignited its global campaign, ‘Go All Out’, unleashing a bold celebration of rugby’s fandom, epic entertainment, global unity and the passion that will power Australia’s hosting of the world’s biggest ever rugby tournament.

-

![]()

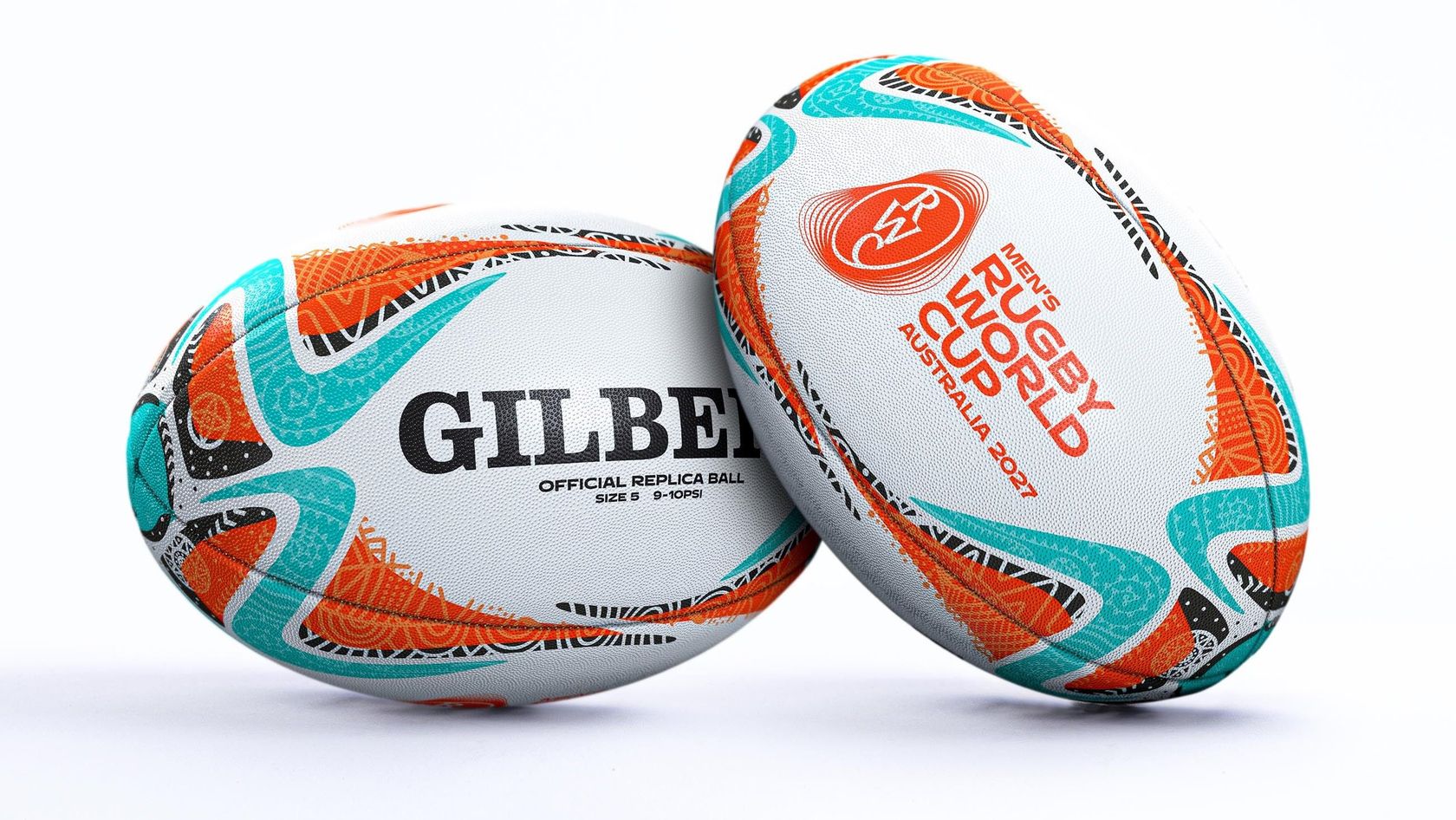

Media release Official match ball design unveiled for Rugby World Cup 2027 as Gilbert extends long-term partnership with World Rugby until 2033

World Rugby and Gilbert have today announced the unveiling of the official match ball design for the Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 in Australia, alongside confirmation of a landmark extension to their long-standing partnership through to 2033.

-

![]()

RWC 2027 All you need to know about the draw, format, pools and dates

The Men's Rugby World Cup 2027 Draw will take place on Wednesday, 3 December and the format for the expanded edition with 24 teams has been unveiled.

-

![]()

Media release World Rugby and Emirates announce record-breaking partnership extension

World Rugby and Emirates have announced a landmark multi tournament partnership, the biggest, longest and most wide ranging in the governing body’s history, strengthening a long-standing and globally recognisable relationship that will run across rugby’s premier events through to at least 2035.

-

![]()

SVNS World Rugby expands trials of a new ball for women’s rugby to HSBC SVNS

World Rugby is expanding trials of a new ball for women’s rugby to this years’ HSBC SVNS Series. The new bespoke size 4.5 ball has been developed in partnership with Gilbert to be the same weight as a size 5 whilst maintaining the advanced aerodynamic and technological features.

-

![]()

RWC 2027 Presale dates announced as Jonny Wilkinson and George Gregan reunite for RWC 2027

Anticipation for Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 in Australia reaches new heights today with the announcement of the official ticket presale dates, alongside the launch of a new global campaign teaser featuring two icons of the game, Australia’s George Gregan and England’s Jonny Wilkinson, set to excite fans around the world.

-

![]()

SVNS HSBC SVNS launches in Dubai with destinations for all three levels locked in, stars confirmed and a new format to excite fans

Global energy, superstar talent and a new competition format headline a bold new era for HSBC SVNS, as World Rugby unveils the host cities for the newly expanded second and third divisions.

-

![]()

World Rugby Awards Seven nations represented in the World Rugby Men’s 15s Dream Team of the Year 2025

The final category of the World Rugby Awards 2025 has been revealed today, celebrating the Men’s 15s Dream Team of the Year. This announcement caps off an extraordinary season of international rugby and sets the stage for a new era beginning in 2026, with the launch of the inaugural World Rugby Nations Cup and Nations Championship.

-

![]()

Disciplinary Independent disciplinary update: Vlad Neculau (Romania)

Vlad Neculau has been suspended for four matches (reduced to three on successful completion of the Coaching Intervention Programme) after a Foul Play Review Committee considered the red card issued during the November international match between Romania and Uruguay on Saturday, 22 November.

-

![]()

World Rugby Awards World Rugby Awards 2025: Malcolm Marx, Fabian Holland and Santiago Pedrero headline men’s category winners

Rugby’s brightest stars were celebrated today during an exciting day of international test rugby, with South Africa’s Malcolm Marx, New Zealand’s Fabian Holland and Chile’s Santiago Pedrero taking home top honours in the men’s categories.

-

![]()

Discplinary Independent disciplinary update: Sergio Manoel Silveira de Luna (Brazil)

Sergio Manoel Silveira de Luna (Brazil) has been suspended for three matches (reduced to two on successful completion of the Coaching Intervention Programme) after a Foul Play Review Committee considered the red card issued to him.

-

![]()

RWC 2027 Official Travel Agents appointed for Men's Rugby World Cup Australia 2027

Men’s Rugby World Cup 2027 (RWC 2027) and Sports Travel & Hospitality (STH), a Sodexo Live! Company trading as Rugby World Cup Experiences (RWCE) have announced the list of Official Travel Agents (OTAs) exclusively authorised to sell ticket-inclusive travel packages for RWC 2027 taking place in Australia (1 October – 13 November 2027).

-

![]()

SVNS HSBC SVNS Series to debut in New York

World Rugby and USA Rugby, in partnership with TEG Rugby Live, have announced New York as the host of the HSBC SVNS series leg in the United States. From 14-15 March, 2026, the world’s premier sevens competition will take centre stage at Sports Illustrated Stadium.